How to Scale Your Model

A Systems View of LLMs on TPUs (Part 0: Intro | Part 1: Rooflines)

Training LLMs often feels like alchemy, but understanding and optimizing the performance of your models doesn't have to. This book aims to demystify the science of scaling language models: how TPUs (and GPUs) work and how they communicate with each other, how LLMs run on real hardware, and how to parallelize your models during training and inference so they run efficiently at massive scale. If you've ever wondered “how expensive should this LLM be to train” or “how much memory do I need to serve this model myself” or “what's an AllGather”, we hope this will be useful to you.

Much of deep learning still boils down to a kind of black magic, but optimizing the performance of your models doesn’t have to — even at huge scale! Relatively simple principles apply everywhere — from dealing with a single accelerator to tens of thousands — and understanding them lets you do many useful things:

- Ballpark how close parts of your model are to their theoretical optimum.

- Make informed choices about different parallelism schemes at different scales (how you split the computation across multiple devices).

- Estimate the cost and time required to train and run large Transformer models.

- Design algorithms that take advantage of specific hardware affordances.

- Design hardware driven by an explicit understanding of what limits current algorithm performance.

Expected background: We’re going to assume you have a basic understanding of LLMs and the Transformer architecture but not necessarily how they operate at scale. You should know the basics of LLM training and ideally have some basic familiarity with JAX. Some useful background reading might include this blog post on the Transformer architecture and the original Transformer paper. Also check out this list for more useful concurrent and future reading.

Goals & Feedback: By the end, you should feel comfortable estimating the best parallelism scheme for a Transformer model on a given hardware platform, and roughly how long training and inference should take. If you don’t, email us or leave a comment! We’d love to know how we could make this clearer.

You might also enjoy reading the new Section 12 on NVIDIA GPUs!

Why should you care?

Three or four years ago, I don’t think most ML researchers would have needed to understand any of the content in this book. But today even “small” models run so close to hardware limits that doing novel research requires you to think about efficiency at scale.

The goal of “model scaling” is to be able to increase the number of chips used for training or inference while achieving a proportional, linear increase in throughput. This is known as “strong scaling”. Although adding additional chips (“parallelism”) usually decreases the computation time, it also comes at the cost of added communication between chips. When communication takes longer than computation we become “communication bound” and cannot scale strongly.

Our goal in this book is to explain how TPU (and GPU) hardware works and how the Transformer architecture has evolved to perform well on current hardware. We hope this will be useful both for researchers designing new architectures and for engineers working to make the current generation of LLMs run fast.

High-Level Outline

The overall structure of this book is as follows:

Section 1 explains roofline analysis and what factors can limit our ability to scale (communication, computation, and memory). Section 2 and Section 3 talk in detail about how TPUs work, both as individual chips and — of critical importance — as an interconnected system with inter-chip links of limited bandwidth and latency. We’ll answer questions like:

- How long should a matrix multiply of a certain size take? At what point is it bound by compute or by memory or communication bandwidth?

- How are TPUs wired together to form training clusters? How much bandwidth does each part of the system have?

- How long does it take to gather, scatter, or re-distribute arrays across multiple TPUs?

- How do we efficiently multiply matrices that are distributed differently across devices?

Five years ago ML had a colorful landscape of architectures — ConvNets, LSTMs, MLPs, Transformers — but now we mostly just have the Transformer

Section 5: Training and Section 7: Inference are the core of this book, where we discuss the fundamental question: given a model of some size and some number of chips, how do I parallelize my model to stay in the “strong scaling” regime? This is a simple question with a surprisingly complicated answer. At a high level, there are 4 primary parallelism techniques used to split models over multiple chips (data, tensor, pipeline, and expert), and a number of other techniques to reduce the memory requirements (rematerialisation, optimizer/model sharding (aka ZeRO), host offload, gradient accumulation). We discuss many of these here.

We hope by the end of these sections you should be able to choose among them yourself for new architectures or settings. Section 6 and Section 8 are practical tutorials that apply these concepts to LLaMA 3, a popular open-source model.

Finally, Section 9 and Section 10 look at how to implement some of these ideas in JAX and how to profile and debug your code when things go wrong. Section 12 is a new section that dives into GPUs as well.

Throughout we try to give you problems to work for yourself. Please feel no pressure to read all the sections or read them in order. And please leave feedback. For the time being, this is a draft and will continue to be revised. Thank you!

We’d like to acknowledge James Bradbury and Blake Hechtman who derived many of the ideas in this book.

Without further ado, here is Section 1 about TPU rooflines.

Links to Sections

This series is probably longer than it needs to be, but we hope that won’t deter you. The first three chapters are preliminaries and can be skipped if you’re already familiar with the material, although they introduce notation used later. The final three parts might be the most practically useful, since they explain how to work with real models.

Part 1: Preliminaries

-

Chapter 1: A Brief Intro to Roofline Analysis. Algorithms are bounded by three things: compute, communication, and memory. We can use these to approximate how fast our algorithms will run.

-

Chapter 2: How to Think About TPUs. How do TPUs work? How does that affect what models we can train and serve?

-

Chapter 3: Sharded Matrices and How to Multiply Them. Here we explain model sharding and multi-TPU parallelism by way of our favorite operation: (sharded) matrix multiplications.

Part 2: Transformers

-

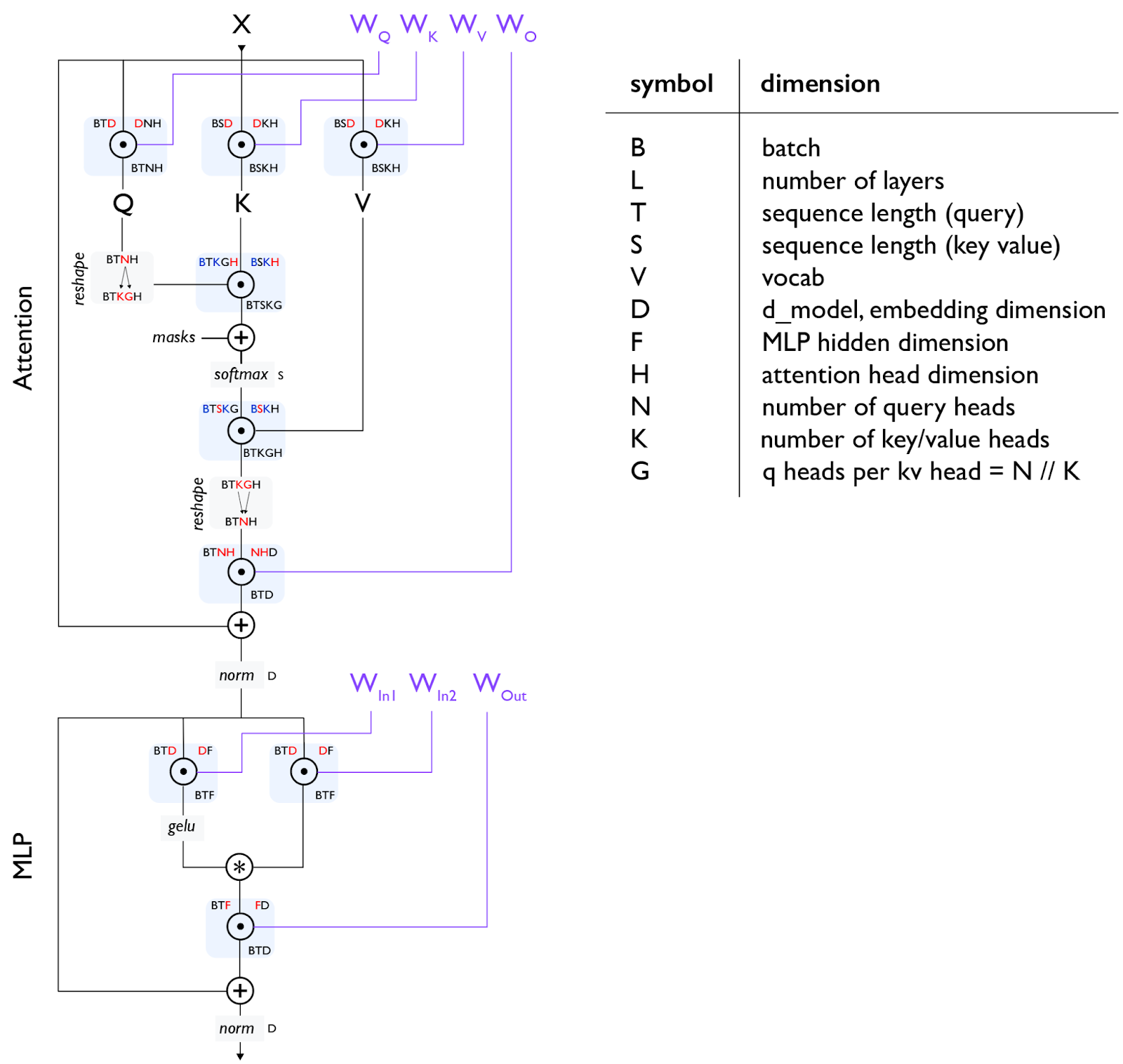

Chapter 4: All the Transformer Math You Need to Know. How many FLOPs does a Transformer use in its forward and backward pass? Can you calculate the number of parameters? The size of its KV caches? We work through this math here.

-

Chapter 5: How to Parallelize a Transformer for Training. FSDP. Megatron sharding. Pipeline parallelism. Given some number of chips, how do I train a model of a given size with a given batch size as efficiently as possible?

-

Chapter 6: Training LLaMA 3 on TPUs. How would we train LLaMA 3 on TPUs? How long would it take? How much would it cost?

-

Chapter 7: All About Transformer Inference. Once we’ve trained a model, we have to serve it. Inference adds a new consideration — latency — and changes up the memory landscape. We’ll talk about how disaggregated serving works and how to think about KV caches.

-

Chapter 8: Serving LLaMA 3 on TPUs. How much would it cost to serve LLaMA 3 on TPU v5e? What are the latency/throughput tradeoffs?

Part 3: Practical Tutorials

-

Chapter 9: How to Profile TPU Code. Real LLMs are never as simple as the theory above. Here we explain the JAX + XLA stack and how to use the JAX/TensorBoard profiler to debug and fix real issues.

-

Chapter 10: Programming TPUs in JAX. JAX provides a bunch of magical APIs for parallelizing computation, but you need to know how to use them. Fun examples and worked problems.

Part 4: Conclusions and Bonus Content

-

Chapter 11: Conclusions and Further Reading. Closing thoughts and further reading on TPUs and LLMs.

-

Chapter 12: How to Think About GPUs. A bonus section about GPUs, how they work, how they’re networked, and how their rooflines differ from TPUs.